|

This article was originally published here.

The increase in food takeout due to the pandemic has also led to an increase in single-use plastic items. This is particularly relevant when it comes to the increase in takeout food packaging as well as the use of non-reusable silverware, cups or plates, even when dining in. Food waste itself, which can include the spoiling of food or food that is just thrown away, is already a problem in the U.S. According to the US Department of Agriculture, food waste accounts for 30-40% of the food supply. “As an industry as far as sustainability goes, this was almost like a step back,” said Constante Joseph Agbannawag, the sustainability program coordinator at the Office of Sustainability at the University of Arizona. “A lot of different places around the world and around the country saw an uptick in single-use plastics.” The spread of the coronavirus was unknown during the beginning of the pandemic. Customers, as well as employees, wanted to feel safer about how they were handling the food they bought at restaurants or the coffee from a cafe. In order to ensure this, businesses avoided their usual washable utensils or cups. “A couple of months into the pandemic, though, we did start seeing reports that said reusables are safe and are a thing that can be utilized as long as we sanitize properly between uses,” Agbannawag said. However, Agbannawag said that proper sanitation cannot always be assumed. He also said that the public perception when it comes to touching something someone else has touched remains concerning. Compost Cats, a composting program run through the Office of Sustainability at the UA, is working with the city of Tucson to take compost not only from the UA Student Unions but also from businesses around Tucson. Composting is a way to divert food waste from landfills by converting food scraps along with leaves or branches into plant fertilizer. “Compost Cats is now working with the Unions and Office of Sustainability to identify how we can buy more compostable single-use items. There’s a big distinction between bioplastics and compostable items, and we’re trying to work with the Unions to really identify what single-use items like clamshells or straws or silverware that we can buy and give to students that can then be composted,” Agbannawag said. Ray Flores, president of Flores Concepts which owns El Charro as well as Charro Steak, Charro del Rey, Charrovida and Barrio Charro, said that 90 percent of their packaging is environmentally friendly. Before the pandemic, Flores Concepts made efforts to convert most of their takeout program into sustainable packaging. Since the pandemic, keeping up with this commitment to sustainable packaging has been costly as supply chains have been struggling. According to Flores, this could be due to reduced labor or shutdowns in manufacturing facilities. It also could be the result of high demand in general as the industry attempts to move toward sustainable packaging. “We may have had something that we thought was a solution, and all of a sudden, we don’t have it anymore. Things that may come out of other parts of the world are hard to get,” Flores said. The El Charro restaurants did have to transition their utensils, as well as their menus, to single-use when dining in. “During the pandemic, we definitely went through a lot of those kinds of items because that’s what people needed to feel secure that things weren’t touched or washed,” Flores said. However, the takeout packaging at Barrio Charro, a fast-casual Flores Concepts restaurant that opened during the pandemic, is entirely sustainable according to Flores. Currently, the El Charro restaurants, as other restaurants may be, are in the process of transitioning back into the normal balance of dine-in and takeout orders. However, the restaurant is not entirely back to where it was. Still, about 20-30 percent of their sales are takeout. During a normal time, this would be around 10-15 percent, according to Flores. “The pandemic winding down, if you will, has created a surge of business, but it's also created a surge of issues that make it hard to be as efficient and profitable as we should be,” Flores said.

0 Comments

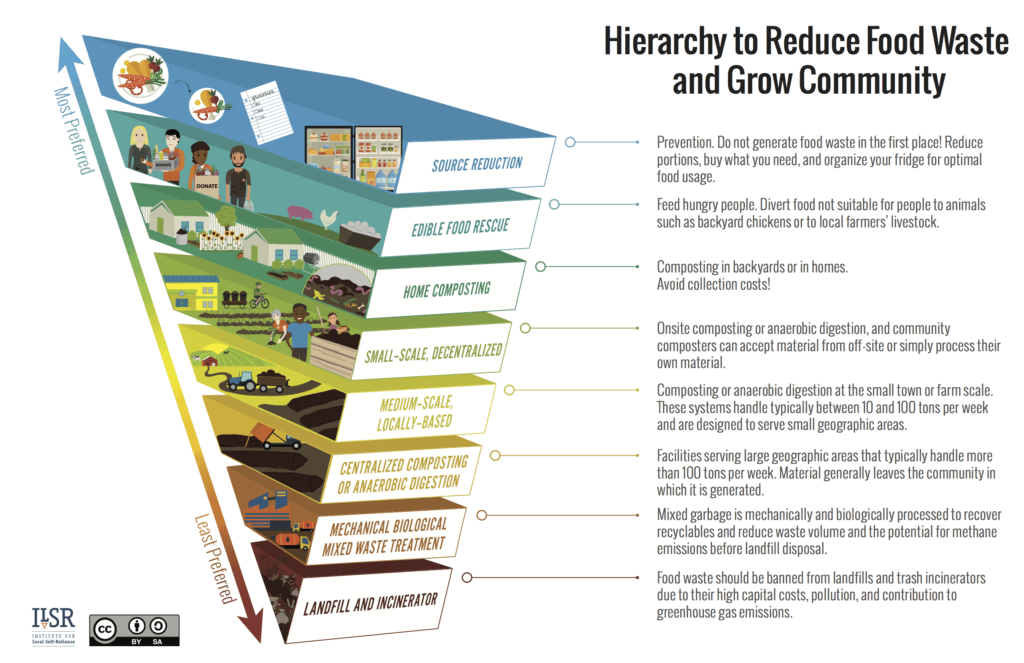

The following comes from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (www.ilsr.org), a national nonprofit organization working to strengthen local economies, and redirect waste into local recycling, composting, and reuse industries. It is reprinted here with permission. We’ve developed this Hierarchy to Reduce Waste & Grow Community in order to highlight the importance of locally based composting solutions as a first priority over large-scale regional solutions. Composting can be small scale and large scale and everything in between but too often home composting, onsite composting, community scale composting, and on-farm composting are overlooked. Anaerobic digestion systems come in different sizes as well. This new hierarchy addresses issues of scale and community benefits when considering what strategies and infrastructure to pursue for food waste reduction and recovery. The US Environmental Protection Agency has long been a strong advocate of food waste recovery. Its Food Waste Reduction Hierarchy has been widely disseminated and even written into local law. Vermont’s Universal Recycling Law, for instance, has made it the policy of that state. More recently, in 2015, EPA joined with the US Department of Agriculture, in establishing the first ever domestic goal to reduce food loss and waste by half by the year 2030. The agency’s hierarchy remains an important guideline for how this goal is to be met: prevent food waste, feed hungry people, feed animals, and recover via industrial uses and anaerobic digestion. However, in the EPA’s hierarchy, composting is listed just before disposal via landfilling and incineration. We believe size matters. ILSR supports the development of a diverse and distributed food waste reduction and recovery infrastructure. We hope local and state governments will consider using our hierarchy as a policy framework. We welcome comments and suggestions. Check out the slideshow linked below: https://www.slideshare.net/ILSR/hierarchy-to-reduce-food-waste-and-grow-community This was originally posted at BBC Good Food. Please go here to read the original article. Issues of packaging, food waste and sustainable practices are complex. At Good Food, we are trying to find realistic solutions to the problem of food waste and packaging generated by our test kitchen and members of the team are taking on green challenges at home. Find out the main things we’ve learned with some realistic suggestions for how you can reduce your own household food waste. If you only do one thing – try not to buy too much, and when you choose produce, don’t overlook the wonky fruit and veg. We’ve also got plenty of ideas for how to use your leftovers. Where food is wasted

How we can waste less food

According to the latest figures from WRAP, by weight, household food waste makes up around 70% of the UK post-farm-gate total. They estimate that by cutting food waste each household could save up to £700 per year as well as making less waste. Top 5 ways to cut down on food waste

You can also consider home composting. How we’re tackling food waste at Good Food We test around 80 recipes a month as well as making videos and taking pictures of food and products that come in all sorts of packaging, and we also make waste as we cook. To tackle this, we eat all of the food that comes out of the test kitchen within the company, so when we talk about waste, we mean peelings, offcuts and – on the rare occasion that a recipe goes horribly wrong and is inedible – a complete dish. Each Friday staff take unused ingredients home and we challenge our cookery assistant Liberty to make lunch using as many leftovers as possible. Here’s how our magazines editor got on when challenged to reduce his household food waste over two weeks… How I reduced food waste Keith Kendrick, magazines editor: “As a dad and a foodie, I’m used to cooking family meals. I batch cook the kids’ meals, but prefer to cook on a whim for my wife and me. We normally throw out three small caddy-sacks of food waste a week. My strategy was two-fold: planning meals and creative use of leftovers.” Week one “I wrote out two plans for the week – one for kids, one for adults – and ordered lots of ingredients. At the weekend, I cooked the kids’ weeknight meals, plus a dozen jars of soup for my wife and me to take to work. Ever tried roasting a whole cauliflower, stalks and all, then blitzing it with coconut milk and spices? Delicious! I used the stalks of kale and broccoli, too – lovely when roasted with Marmite. Our Sunday chicken provided enough leftovers to make a curry, a salad and sandwiches for the kids. We still had a fair bit of waste, but none of it could’ve been eaten.” Week two By week two, we had a rhythm – whatever my kids didn’t finish for dinner, my wife had for lunch the next day. The problem? She wasn’t eating the soups I had so lovingly prepared! I thought about freezing them, only my freezer was already full. It was time for an inventory. I took everything out, which provided the meals for the week. Overall, there were only two disasters: a lasagne declared ‘inedible’ by my wife, and a vegan, gluten-free pie that tasted like plasterboard – a total of 263g of food that we could have eaten. All other waste was unavoidable, and we went from three caddy-sacks to two per week. The verdict A success… sort of. Planning was fun, and knowing that 96% of what we threw away was unavoidable made me feel good. However, as a spontaneous cook, it was stifling to plan meals so far in advance. The way forward for us is balance – planning the kids’ meals ahead, with more educated portion sizes, and deciding on the day what my wife and I fancy for dinner, with one eye on the leftovers. This article was originally published at Foodprint.org. Please go here to read the original article.

America wastes roughly 40 percent of its food.1 Of the estimated 125 to 160 billion pounds of food that goes to waste every year, much of it is perfectly edible and nutritious. Food is lost or wasted for a variety of reasons: bad weather, processing problems, overproduction and unstable markets cause food loss long before it arrives in a grocery store, while overbuying, poor planning and confusion over labels and safety contribute to food waste at stores and in homes.2 Food waste also has a staggering price tag, costing this country approximately $218 billion per year.3 Uneaten food also puts unneeded strain on the environment by wasting valuable resources like water and farmland. At a time when 12 percent of American households are food insecure 4, reducing food waste by just 15 percent could provide enough sustenance to feed more than 25 million people, annually.5 What Is Wasted Food? There are two main kinds of wasted food: food loss and food waste. Food loss is the bigger category, and incorporates any edible food that goes uneaten at any stage. In addition to food that’s uneaten in homes and stores, this includes crops left in the field, food that spoils in transportation, and all other food that doesn’t make it to a store. Some amount of food is lost at nearly every stage of food production.6 Food waste is a specific piece of food loss, which the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS), defines as food discarded by retailers due to color or appearance and plate waste by consumers.”7 Food waste includes the half-eaten meal left on the plate at a restaurant, food scraps from preparing a meal at home and the sour milk a family pours down the drain. 8 WASTE LESS WHEN YOU COOK COOKING SUSTAINABLY Where Is Food Lost? Edible food is discarded at every point along the food chain: on farms and fishing boats, during processing and distribution, in retail stores, in restaurants and at home. 9 Food Loss on Farms Food production in the US uses 15.7 percent of the total energy budget, 50 percent of all land and 80 percent of all freshwater consumed. 101112 Yet 20 billion pounds of produce is lost on farms every year. 13 Food loss occurs on farms for a variety of reasons. To hedge against pests and weather, farmers often plant more than consumers demand. Food may not be harvested because of damage by weather, pests and disease. Market conditions off the farm can lead farmers to throw out edible food. If the price of produce on the market is lower than the cost of transportation and labor, sometimes farmers will leave their crops un-harvested. This practice, called dumping, happens when farmers are producing more of a product that people are willing to buy, or when demand for a product falls unexpectedly. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, farmers lost a major portion of their business due to restaurant and school lunchroom closures. This led them to the painful decision to plow over edible crops and dump up to 3.7 million gallons of milk per day onto fields rather than go through the additional cost of harvesting and processing products they could not sell.14 While the government has programs to buy excess produce and donate it to food shelves and emergency relief organizations, the highly specialized processing and transportation networks for many products makes donation difficult and expensive.15 Cosmetic imperfections (leading to so-called “ugly produce”) are another significant source of food waste on farms both before and after harvest, as consumers are less interested in misshaped or blemished items. Food safety scares and improper refrigeration and handling can also force farmers to throw out otherwise edible food. 16 Finally, in recent years, farmers have been forced to leave food in the fields due to labor shortages caused by changing immigration laws. 17 Food Loss on Fishing Boats A recent study by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that eight percent of the fish caught in the world’s marine fisheries is discarded — about 78.3 million tons per year. 18 Discards are the portion of the catch of fish that are not retained and are often returned dead or dying back into the water. 19 Other studies estimate that 40 to 60 percent of the fish caught by European trawlers in the North Sea are discarded at sea. 2021 And a recent US study found that 16 to 32 percent of bycatch are thrown away by American commercial fishing boats. 22 Tropical shrimp trawling has the highest discard rate and accounts for over 27 percent of total estimated discards. 23 Discarding throws the ocean’s ecosystem off balance by increasing food for scavengers and killing large numbers of target and non-target fish species. 24 Food Loss in Produce Packing Houses Some produce that does not meet strict retailer or consumer cosmetic standards goes to suppliers for processing, but even if they are willing to accept the produce, the supplier must be close enough to justify transportation costs and able to accept large volumes of produce. These cost barriers make it particularly challenging for small and midsize farmers to get these secondary items to processors. 25 Of the estimated 125 to 160 billion pounds of food that goes to waste every year, much of it is perfectly edible and nutritious. Food Loss in Manufacturing Facilities Most waste at manufacturing and processing facilities is generated while trimming off edible portions, such as skin, fat, crusts and peels from food. Some of this is recovered and used for other purposes — in the US, about 33 percent of food waste from manufacturing goes to animal feed.26 Even with this recovered and reused material taken out of the calculation, about two billion pounds of food are wasted in the food processing or manufacturing stage.27 A number of issues, like overproduction, product damage and technical problems at manufacturing facilities contribute to these large quantities of food waste.28 Much like farms, food processing facilities are vulnerable to labor disruptions and shortages. During the COVID-19 outbreak, many meat processing facilities closed as workers fell ill, which forced processing plants to close. This meant that the animals, which could no longer be processed, were slaughtered and discarded by the thousand.29 Food Loss in Transportation and Distribution Networks During food transportation and distribution, perishable foods are vulnerable to loss, especially in developing nations where access to adequate and reliable refrigeration, infrastructure and transportation can be a challenge. While this is not a significant source of food waste in the US; food waste does occur when produce spoils from improper refrigeration. 30 A larger problem occurring at this stage is the rejection of perishable food shipments, which are thrown out if another buyer can’t be found quickly. It is estimated that between two and five percent of food shipments are rejected by food buyers. 31 Even if these goods make it to market, they are often wasted anyway because of shorter shelf lives. Often, rejected food shipments are donated to food rescue organizations, but the quantities are too large to accept. 32 Where is Food Wasted? Food Waste in Retail Businesses An estimated 43 billion pounds of food were wasted in US retail stores in 2010. 33 This is particularly disconcerting given that in 2016, 12.3 percent of American households were food insecure. 34 Most of the loss in retail operations is in perishables, including baked goods, produce, meat, seafood and prepared meals. 35 The USDA estimates that supermarkets lose $15 billion annually in unsold fruit and vegetables alone. 36 Unfortunately, wasteful practices in the retail industry are often viewed as good business strategies. Some of the main drivers for food loss at retail stores include: overstocked product displays, expectation of cosmetic perfection of fruits, vegetables and other foods, oversized packages, the availability of prepared food until closing, expired “sell by” dates, damaged goods, outdated seasonal items, over purchasing of unpopular foods and under staffing. 37 Currently, only 10 percent of edible wasted food is recovered each year, in the US. 38 Barriers to recovering food are liability concerns, distribution and storage logistics and funds needed for gleaning, collecting, packaging and distribution. The Good Samaritan Food Donation Act, signed into law in 1996, provides legal liability protection for food donors and recipients and tax benefits for participating businesses. However, awareness about this law and trust in the protections it offers remains low. 39 15 EASY WAYS TO REDUCE FOOD WASTE WHAT TO KNOW BEFORE YOU THROW Food Waste in Restaurants and Institutions US restaurants generate an estimated 22 to 33 billion pounds of food waste each year. Institutions — including schools, hotels and hospitals — generate an additional 7 to 11 billion pounds per year. 40 Approximately 4 to 10 percent of food purchased by restaurants is wasted before reaching the consumer. Drivers of food waste at restaurants include oversized portions, inflexibility of chain store management and extensive menu choices. 41 According to the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab, on average, diners leave 17 percent of their meals uneaten and 55 percent of edible leftovers are left at the restaurant. 42 This is partly due to the fact that portion sizes have increased significantly over the past 30 years, often being two to eight times larger than USDA or Federal Drug Administration (FDA) standard servings. Kitchen culture and staff behavior such as over-preparation of food, improper ingredient storage and failure to use food scraps and trimmings can also contribute to food loss. 43 All-you-can-eat buffets are particularly wasteful, since extra food cannot legally be reused or donated due to health code restrictions. 44 The common practice of keeping buffets fully stocked during business hours (rather than allowing items to run out near closing) creates even more waste. Food Waste in Households Households are responsible for the largest portion of all food waste. ReFED estimates that US households waste 76 billion pounds of food per year. 45 Approximately 40 to 50 percent of food waste (including 51 to 63 percent of seafood waste 46 happens at level of the consumer. 47 In the US, an average person wastes 238 pounds of food per year (21 percent of the food they buy), costing them $1,800 per year. 48 In terms of total mass, fresh fruits and vegetables account for the largest losses at the consumer level (19 percent of fruits and 22 percent of vegetables), followed by dairy (20 percent), meat (21 percent) and seafood (31 percent). 49 Major contributors to household food waste include:

COMPOSTING 101 HOW TO GET STARTED The Biggest Reasons Food Gets Wasted There are several macro-level drivers of the food waste problem in the US and globally. One is the difficulty of turning new consumer awareness into action. Public awareness about food waste in the US has improved significantly over the last few years. This is largely due to the efforts of organizations like the Ad Council and their Save the Food campaign, and coverage of the topic from Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, National Geographic, BBC, Consumer Reports and the more than 3,300 articles written about the issue by major news and business outlets between 2011 and 2016 — a 205 percent increase over that period. 58 Additionally, in 2015, the USDA and the US Environmental Protection Agency adopted federal targets to cut food waste by 50 percent by 2030. 59 In 2016 a survey by the Ad Council of 6700 adults, 75 percent of respondents said that food waste was important or very important to them. However, limited data makes it difficult to assess whether this awareness has turned into action and whether or not people are actually wasting less food now than they were before. Homes remain a large source of food waste and more needs to be done to help educate the public and provide people with resources to help them implement food saving practices at home. 60 Another reason why food waste has become such a large problem is that it has not been effectively measured or studied. A comprehensive report on food losses in the US is needed to characterize and quantify the problem, identify opportunities and establish benchmarks against which progress can be measured. A study of this type by the European Commission in 2010 proved to be an important tool for establishing reduction goals in Europe and can serve as a model for US policymakers. 61 What Are the Environmental Impacts of Food Waste? Only five percent of food is composted in the US and as a result, uneaten food is the single largest component of municipal solid waste. 62 In landfills, food gradually breaks down to form methane, a greenhouse gas that’s up to 86 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. 63 According to a report from the UK based organization WRAP, if food were removed from UK landfills, the greenhouse gas abatement would be equivalent to removing one-fifth of all the cars in the UK from the road. 64 Consumer food waste also has serious implications for energy usage. A study by the consulting group McKinsey found that, on average, household food losses are responsible for eight times the energy waste of farm-level food losses due to the energy used along the food supply chain and in preparation. 65 In addition, food waste is responsible for more than 25 percent of all the freshwater consumption in the US each year, and is among the leading causes of fresh water pollution. 66 Given all the resources demanded for food production, it is worth our while to make sure that the food we produce is not wasted. The following information is from the Food Secure Canada website. Go here to read the full article and to learn more about the importance of Food Sovereignty.

"Food Sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems." FOOD SECURITY IS A GOAL WHILE FOOD SOVEREIGNTY DESCRIBES HOW TO GET THERE. THEY DIFFER IN SOME KEY WAYS.

SEVEN PILLARS OF FOOD SOVEREIGNTY The first six pillars were developed at the International Forum for Food Sovereignty in Nyéléni(link is external), Mali, in 2007. The seventh pillar – Food is Sacred - was added by members of the Indigenous Circle during the People’s Food Policy process. 1. FOCUSES ON FOOD FOR PEOPLE

2. BUILDS KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS

3. WORKS WITH NATURE

4. VALUES FOOD PROVIDERS

5. LOCALIZES FOOD SYSTEMS

6. PUTS CONTROL LOCALLY

7. FOOD IS SACRED

This article is shared from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Please go here to read the original article.

Direct economic costs of $750 billion annually – Better policies required, and “success stories” need to be scaled up and replicated 11 September 2013, Rome - The waste of a staggering 1.3 billion tonnes of food per year is not only causing major economic losses but also wreaking significant harm on the natural resources that humanity relies upon to feed itself, says a new FAO report. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources is the first study to analyze the impacts of global food wastage from an environmental perspective, looking specifically at its consequences for the climate, water and land use, and biodiversity. Among its key findings: Each year, food that is produced but not eaten guzzles up a volume of water equivalent to the annual flow of Russia's Volga River and is responsible for adding 3.3 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases to the planet's atmosphere. And beyond its environmental impacts, the direct economic consequences to producers of food wastage (excluding fish and seafood) run to the tune of $750 billion annually, FAO's report estimates. "All of us - farmers and fishers; food processors and supermarkets; local and national governments; individual consumers -- must make changes at every link of the human food chain to prevent food wastage from happening in the first place, and re-use or recycle it when we can't," said FAO Director-General José Graziano da Silva. "We simply cannot allow one-third of all the food we produce to go to waste or be lost because of inappropriate practices, when 870 million people go hungry every day," he added. As a companion to its new study, FAO has also published a comprehensive "tool-kit" that contains recommendations on how food loss and waste can be reduced at every stage of the food chain. The tool-kit profiles a number of projects around the world that show how national and local governments, farmers, businesses, and individual consumers can take steps to tackle the problem. Achim Steiner, UN Environment Programme (UNEP) Executive Director, said: "UNEP and FAO have identified food waste and loss --food wastage-- as a major opportunity for economies everywhere to assist in a transition towards a low carbon, resource efficient and inclusive Green Economy. Today's excellent report by FAO underlines the multiple benefits that can be realized-- in many cases through simple and thoughtful measures by for example households, retailers, restaurants, schools and businesses-- that can contribute to environmental sustainability, economic improvements, food security and the realization of the UN Secretary General's Zero Hunger Challenge. We would urge everyone to adopt the motto of our joint campaign: Think Eat Save - Reduce Your Foodprint!". UNEP and FAO are founding partners of the Think Eat Save - Reduce Your Foodprint campaign that was launched earlier in the year and whose aim is to assist in coordinating worldwide efforts to manage down wastage. Where wastage happens Fifty-four percent of the world's food wastage occurs "upstream" during production, post-harvest handling and storage, according to FAO's study. Forty-six percent of it happens "downstream," at the processing, distribution and consumption stages. As a general trend, developing countries suffer more food losses during agricultural production, while food waste at the retail and consumer level tends to be higher in middle- and high-income regions -- where it accounts for 31-39 percent of total wastage -- than in low-income regions (4-16 percent). The later a food product is lost along the chain, the greater the environmental consequences, FAO's report notes, since the environmental costs incurred during processing, transport, storage and cooking must be added to the initial production costs. Hot spots Several world food wastage "hot-spots" stand out in the study: Wastage of cereals in Asia is a significant problem, with major impacts on carbon emissions and water and land use. Rice's profile is particularly noticeable, given its high methane emissions combined with a large level of wastage. While meat wastage volumes in all world regions is comparatively low, the meat sector generates a substantial impact on the environment in terms of land occupation and carbon footprint, especially in high-income countries and Latin America, which in combination account for 80 percent of all meat wastage. Excluding Latin America, high-income regions are responsible for about 67 percent of all meat wastage Fruit wastage contributes significantly to water waste in Asia, Latin America, and Europe, mainly as a result of extremely high wastage levels. Similarly, large volumes of vegetable wastage in industrialized Asia, Europe, and South and South East Asia translates into a large carbon footprint for that sector. Causes of food wastage - and options for addressing them A combination of consumer behavior and lack of communication in the supply chain underlies the higher levels of food waste in affluent societies, according to FAO. Consumers fail to plan their shopping, overpurchase, or over-react to "best-before-dates," while quality and aesthetic standards lead retailers to reject large amounts of perfectly edible food. In developing countries, significant post-harvest losses in the early part of the supply chain are a key problem, occurring as a result of financial and structural limitations in harvesting techniques and storage and transport infrastructure, combined with climatic conditions favorable to food spoilage. To tackle the problem, FAO's toolkit details three general levels where action is needed: High priority should be given to reducing food wastage in the first place. Beyond improving losses of crops on farms due to poor practices, doing more to better balance production with demand would mean not using natural resources to produce unneeded food in the first place. In the event of a food surplus, re-use within the human food chain-- finding secondary markets or donating extra food to feed vulnerable members of society-- represents the best option. If the food is not fit for human consumption, the next best option is to divert it for livestock feed, conserving resources that would otherwise be used to produce commercial feedstuff. Where re-use is not possible, recycling and recovery should be pursued: by-product recycling, anaerobic digestion, compositing, and incineration with energy recovery allow energy and nutrients to be recovered from food waste, representing a significant advantage over dumping it in landfills. Uneaten food that ends up rotting in landfills is a large producer of methane, a particularly harmful GHG. Funding for the Food Wastage Footprint report and toolkit was provided by the government of Germany. Read in more detail about FAO's specific recommendations for reducing food wastage. This article is shared from National Geographic. Please go here to read the original post. Editor's Note: Tristram Stuart is one of National Geographic's 2014 Emerging Explorers, part of a program that honors tomorrow's visionaries—those making discoveries, making a difference, and inspiring people to care about the planet. Tristram Stuart thinks we should do something revolutionary with food: Eat it. The British author calls the problem of food waste "scandalous and grotesque" and cites statistics to prove it: One-third of the world's food is wasted from plough to plate. The planet's one billion hungry people could be lifted out of malnourishment with less than a quarter of the food wasted in the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe. The water used to irrigate food that ends up being thrown away could meet the domestic water needs of nine billion people. Until a few years ago, the colossal scale of food waste was largely unaddressed. But Stuart's 2009 book, Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal, and the grassroots initiatives he launched have lifted the topic from obscurity to prominence worldwide. "We want to catalyze a food-waste revolution one person, one town, one country at a time—helping stop needless hunger and environmental destruction across our planet," he says. VIEW IMAGES As a teen, Tristram Stuart raised pigs. He fed them leftovers from local shops and was shocked by how much food was going to waste. Stuart's passion started with pigs. At age 15, he raised a few pigs to earn extra money, feeding them with leftover food from his school kitchen and local shops. He soon realized that most of the food that went to the pigs was actually fit for human consumption. He also began noticing supermarket garbage bins overflowing with fresh food. "Everywhere I looked, we were hemorrhaging food," he says. "So I began confronting businesses about the waste and exposing it to the public." His research revealed that most rich countries produce between three and four times more food than required to meet their citizens' nutritional needs. Yet one billion people suffer from malnutrition worldwide. "Producing this huge surplus leads to deforestation, depleted water supplies, massive fossil fuel consumption, and biodiversity loss," Stuart says. "Excess food decomposing in landfills accounts for 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions by wealthy nations." In 2009, Stuart launched what has become the flagship event of his global food-waste campaign: Feeding the 5000. Created entirely of food that would otherwise be wasted, the free feast in London has been replicated around the world. "These events give people a clear, tangible idea of food-waste problems and potential solutions right where they live," Stuart says. "A few years ago most big U.K. supermarkets wouldn't even talk to food redistribution charities—today they all do." Stuart has also successfully campaigned for retailers to relax strict cosmetic standards for fruit and vegetables. "Farmers leave up to 40 percent of harvests rotting in fields because their produce doesn't conform to the perfect size or shape big supermarkets demand," Stuart says. "This even happens in countries like Kenya where millions of people are hungry." Food waste “leads to deforestation, depleted water supplies, massive fossil fuel consumption, and biodiversity loss," Stuart says. Since Stuart's efforts began, many supermarkets have changed policies. "Ugly" fruits and vegetables are now the fastest growing sector in the fresh produce market. Since stores can sell them for less, shoppers get a bargain. In 2013, U.K. farmers sold 300,000 tons of produce that would once have been rejected, an increase of 20 percent for many growers. Farmers have benefited from Stuart's actions in other ways as well. Previously, if supermarkets cut back on their produce order at the last moment, farmers bore the cost. After Stuart and other organizations spotlighted the problem, legislation was passed to force U.K. retailers to share the burden. "Now [supermarkets] have an incentive to improve forecasts and hence curb waste," says Stuart. Even so, some produce is still left in fields to rot. Stuart's Gleaning Network sends thousands of volunteers to harvest that surplus food, which is then distributed to the hungry. The network has expanded across the U.K. and France, and will soon launch in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. Stuart has not forgotten his porcine roots. Another project, The Pig Idea, seeks to change laws that restrict using food waste to feed pigs. "Pigs were originally domesticated for the sole purpose of recycling human food waste back into food," says Stuart, "a process that has worked for thousands of years." These days, many countries "import millions of tons of soy from South America to feed pigs—causing massive deforestation throughout the Amazon," he says. "We also feed pigs wheat and maize, which hungry people in Africa and Asia could eat." His initiative calls for a strongly regulated system that would allow pigs to be safely fed food waste once again. The campaign has inspired supermarkets to send waste that is legal for livestock, such as bread, to farms rather than landfills. "Feeding food waste to pigs saves 20 times more carbon than the next-best recycling method," he says. Stuart works with a small team in London, devising and testing ideas, then sharing them with anyone who can replicate and expand them worldwide. "We've become an international hub for sharing knowledge, communicating best practices, and forging collaborations," he says. "The food-waste movement started as a trickle—but today it's a tidal wave." He stresses that each individual can make a powerful difference: "In the U.K., food waste in homes has already decreased 25 percent. "Citizens are the sleeping giant in this equation," adds Stuart. "By rising up and speaking out, we can—and are—making the world's food system less unjust and more sustainable every day." VIEW IMAGES Shared from original article in Chatelaine.

In an effort to reduce food waste, the apps connect buyers with vendors looking to unload good food that would otherwise be thrown away. A shocking amount of restaurant food goes from today’s special to tonight’s trash, but two Canadian-made apps are looking to create a new stop along that path, in an effort to reduce food waste and to save savvy shoppers some dough. About a third of all food produced for human consumption is wasted or lost each year. That works out to a shocking $31 billion worth of food trashedannually in Canada. Enter Ubifood, an app developed by Montreal entrepreneur Caroline Pellegrini. It connects consumers with food vendors looking to sell leftover items for a discounted price at the end of each business day. Pellegrini was inspired to create Ubifood while working in a bakery, where she witnessed just how much food was tossed by closing time. Through the app, vendors upload photos of food they plan to throw out (but is still perfectly fine to eat) and users browse and pay for items online prior to pickup. Users can customize their search based on location and food preferences, and discounts can range from 15 to 80 percent (!) off the regular price. Ubifood, which launched this past spring, has about 5,000 users and currently works with almost 40 vendors across Montreal, from high-end restaurants to cafés and fast food chains. The growing success of the app has inspired another food waste warrior to create something similar in Toronto. Josh Domingues’ Flashfood app will link restaurants and grocers with consumers looking for end-of-day deals. That app is set to launch sometime this month. In an interview with CBC both Pelligrini and Domingues said that if their apps are successful, they’ll expand across the country. Ubifood is available via the App Store and Google Play. Shared from the original article on the David Suzuki Foundation website. You’re eating local, organic, even growing your own food. Make sure you don’t end up throwing out the fruits and vegetables of your hard-earned labour! Besides being a waste of money, time and energy, unused food that ends up in landfills is one of the main sources of greenhouse gases.

Download our handy tip sheet to help you out: DOWNLOAD FIVE WAYS END FOOD WASTE How to not waste food: Meal plan: Take a few minutes to write out a week’s worth of dinners. Start with what’s already on hand. Think about how leftovers can play into lunches, snacks or other meals. Create a grocery list based on your plan. If you prefer electronic help, there are loads of recipe websites — some even create the shopping list! Buy the food you need now. Eat the food you planned. You’ll be rewarded with a clean conscience, a healthier planet and a fatter wallet. Make soup: Veggies make delicious stew, mashed potatoes thicken any stock. Freeze: Freezing food takes only takes a moment and extends the life of what isn’t getting eaten right away. Donate: Swimming in leftovers or perishable garden produce? Bring it to your workplace, local food bank or check online to see which charities take food donations. Create an “Eat-me-first” bin or basket for the fridge: This brilliant, simple tip comes from the Just Eat It movie:

It’s simple: See your food and eat your food! (That’s the whole reason you bought it, right?) Five shopping tips Pick the first one: This goes for things like dairy items. Don’t reach to the back. Grab from the front. Pick the last one: Nobody likes to be picked last. Same goes for the lonely head of lettuce on display. Pick the brown, spotted or crooked ones: Imperfect-looking produce wants to be tasted, not wasted. Choose overripe produce, sometimes: See that pineapple? It’s going to be mouldy tomorrow. And it came all the way from Hawaii! It’s not organic or local but it’s dumpster-bound unless you buy it. Choose single bananas: Grab a few single bananas next time instead of choosing a bunch. Individual action has the power to make a measurable, meaningful difference. Just cutting household food waste in half would immediately save billions.  Bottles of water and still-cold frozen food: Marketplace found garbage bins full of food at Walmart. (CBC) Bottles of water and still-cold frozen food: Marketplace found garbage bins full of food at Walmart. (CBC) This article is re-blogged from CBC Marketplace. Please see the original article here. Doughnuts and pastries. Stalks of still-crunchy celery. Bags of bright, plump oranges. It sounds like a shopping list, but it was all in Walmart's garbage. CBC's Marketplace went through trash bins at two Walmart stores near Toronto to see how much food the company throws away. Over the course of more than 12 visits to the stores, Marketplace staff repeatedly found produce, baked goods, frozen foods, meat and dairy products. Most of the food was still in its packaging, rather than separated for composting. Also in the garbage: bottles of water, frozen cherries that were still cold and tubs of margarine. In a statement, Walmart said it believes the food Marketplace found was unsafe for consumption. In many cases, however, the food was well before its best-before date and appeared to be fresh. Or, if it needed refrigeration or freezing, the food found was still cold. Marketplace staff looked for food waste at all the major retailers, including Costco, Metro, Sobeys, Loblaws and Walmart. While staffers found bins full of food at some Walmart locations, other chains had compactors making it impossible to see what they throw out. Marketplace found cartons of milk days ahead of their best-before date, and Parmesan cheese with months left before it needed to be thrown away. On one trip, Marketplace staff found 12 waist-high bins full of food. After Walmart was contacted, it locked up the bins behind the stores where the food was found. These bags of oranges were found in a Walmart Canada garbage bin on one of 12 trips to a Toronto-area store. (CBC) Ali-Zain Mevawala says he threw out a shopping cart full of produce every day when he managed a Walmart produce and bakery department. Mevawala, formerly with one of the company's Edmonton stores, says if a piece of fruit or vegetable didn't look perfect, it had to be thrown in the trash. "I really felt bad because I know a lot of people in the city or in this country, even in this whole world, they don't even get to eat proper food." 'What's wrong with all those bags of oranges?' Food waste is a worldwide issue. In Canada, a study from Value Chain Management International says across sectors, including at the farm, during processing, in retail stores, restaurants and in homes, $31 billion worth of food is wasted each year. Retailers are responsible for about 10 per cent of that waste, according to the 2014 study. Ali-Zain Mevawala says he threw out a shopping cart full of produce every day when working as a produce and bakery department manager at a Walmart store in Edmonton. (CBC) One of the report's authors says retailers are just doing what buyers expect. "Much of that waste is usually us not willing to buy products that have a blemish in them," says Martin Gooch, CEO of Value Chain Management International. There are challenges in donating food, including location. It's easier to redistribute food in Toronto than in smaller communities, he says. He adds that retailers are working to address in-store processes and training so waste is reduced. Despite laws preventing companies that donate food from being prosecuted if someone gets sick, a key challenge is public opinion, should something happen, says Gooch. CBC Marketplace went through trash bins at two Walmart stores near Toronto to see how much food the company throws away. (CBC) "Someone who'd gotten sick from a product that was donated, that would create a whole bunch of attention … which a retailer or manufacturer has no way of combating." After viewing Marketplace footage, Gooch says the amount of food wastediscovered demonstrated there is "room for improvement." "What's wrong with all those bags of oranges?" he said. Gooch did say some of the items Marketplace uncovered, such as bagged salad, could be unsafe if they had passed their "use by" date. Walmart responds Walmart declined an on-camera interview with Marketplace, but the company sent a statement that said it has many initiatives to decrease food waste throughout the company, including giving unsold food to food banks. After Marketplace contacted Walmart, the company locked up the bins behind the stores where the food was found. (CBC) "On some occasions, food which has not passed its best-before date is deemed unsafe for consumption," Walmart said in its statement. "As a rule we don't place fresh food items on display for sale if the quality is not acceptable." Some of the products may have been returns, the company said. Mevawala says he was given a different reason for the waste when he worked at Walmart. "Once I asked my manager, 'Why do we have to just throw it away? Why can't we just, you know, give it away to some people that really need it?'" he says. "And the manager [said], 'If you just give it away to people, then why are they going to buy it from us?'" Walmart Canada says Mevawala's claim doesn't reflect its approach to food waste. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed